Beginning- thief/work/wife [“She was always heavily made up, like the body in a casket that had been in some terrible accident.” She is aware of thefts. Main character- “All his gestures were exaggerated, like a silent movie star.” They live by the water- “When it grew dark the sky was black and the water alive with pinpoints of light, as if the sea and the sky had changed places.”] Thief in debt to local loan shark.

Middle- selling stolen merchandise to old man who suffered stroke. [“Half of his face moved and spoke, the other half frozen in a smile, as if it were already dead and in heaven.”] Selling doesn’t bring enough $$$ to repay loan.

End- Wife catches him stealing jewellery from her. She leaves him. He contemplates suicide, but realises not enough of a thief to take his own life. [“He did not like to think of death. He had read hundreds of biographies, and always stopped reading before the final chapter.”]

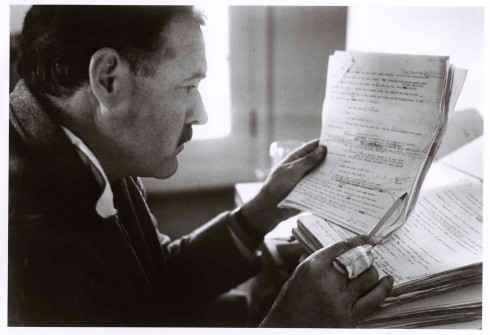

For this draft, write, don’t revise. Remember Hemingway (?) says – first draft of anything is crap.

Theft/The Thief/A Thief By Phillip Begg.

All his life Jim Cahill/Crawley had been told that he had his mother’s eyes, his father’s ears, this or that uncle’s chin or way of walking or laughing. [Change to present simple, more immediate] It is no surprise then that he believes he doesn’t belong to himself. Perhaps this is why he is a thief. Jim works the night shift in a warehouse in Newcastle [too specific?] a small country town. [with aboriginal name- the town was stolen from aborigines.] With the dawn he leaves work with at least ten boxes of shoes in his car. He is a tall man in his twenties [or fifties] with side-swept greying [and or red hair,] a weak chin and thick black-legged spectacles with sad, watery blue eyes stuck to the glass. His family had wanted him to be a priest and he attended a seminary for two years before he was expelled for stealing [wine? money?]. There is still something of the priest about him as he adjusts his glasses constantly, the better to scrutinise the world’s sin. He thought of…[exposition- owes large gambling debt.]

[Use description of drive home from “Glass Umbrella” story, the one rejected by Meanjin, and add here. John arrives home, wakes up wife.]

Description of wife, Jessica- She was pretty in her way, with a face that should have been framed by a veil, for first communion or wedding, he imagined she would be at her happiest then. She reddens at his touch, saying softly, “Oh!” but not to him for her eyes would not quite meet his. Instead, they went to a spot above his left or right shoulder, as if she could see his angel or his the devil there. She looked very kind, and religious and disappointed, like a virgin saint whose martyrdom had been postponed.

[Not bad, but religious theme doesn’t fit. Use old photograph of Helen as reference for wife, the one of her swimming in the ocean on our honeymoon.]

*

“Is that you, John?” Jessica asks sleepily. She often has a cold since and with the snot/phlegm in her throat her breathing sounds like paper being ripped into pieces. He takes off his clothes and sat naked beside her.

“It’s me,” he says.

“Are you sleepy?” she asks him, and he sees her hand moving slowly under her nightgown, over her belly to her loins. [There is a book on the bed beside her.]

She has an anxious guilty beauty, as if it were stolen and she might be required to surrender it at any time. He is not surprised that she is awake, for she can only sleep when she is touching some part of him, his thigh, his arm, his foot, [penis?] as if she needs a handhold of flesh to prevent her from becoming lost in her dreams. Above the bed is the crucifix, which always makes him think of the two thieves crucified with Christ. He always means to find out their names. [Note- look up names in religous encycopedia.]

After a moment she holds her fingers to his nose so he can smell her. [Too explicit perhaps, but want to show the sexual side of their marriage. Copy rest of sex scene from Helen’s journal entry for our honeymoon. They make love. He is careful not to get her pregnant. “Even in erotic dreams, he used contraception.”]

Afterwards, as the light steals in through the curtains, she sees the boxes on the floor.

“John, you promised,” she says.

“Just this once,” he says [biting his nails, his lip] “We need the money.”

“You could go to prison,” she says, holding her belly. [Perhaps she is pregnant- womb as prison]

“I’m careful,” he says. “I stole your heart and got away with it, didn’t I?”

“You didn’t steal it,” she says, smiling despite herself. “I gave it to you.”

[Or]

“Did you?” she said. “I suppose all men are thieves.

[Helen said “All writers are thieves.” Also add her comment, “Forgiving your faults is like painting the Harbour Bridge. As soon as you finish, you have to start over again.” Use later? Have John and Jessica talk for a couple of hundred words more.]

[e.g.]

“Are you happy?” he asks her.

“Yes, I’m happy. I love going to the beach with you, feeling your hand in mine etc etc.” [For rest, quote from Helen’s old love letters.]

[Next day-John goes to sell the stolen shoes.]

John gets in his car, and sweating, drives the short distance to the shop. He parks in an alleyway across from the place. A clumsy hand-painted sign in the dirty window says “All things bought and sold.” The walls of the building are cracked and the red paint is peeling off like sunburnt skin/as if the walls were sunburnt. Outside, on a bench, an old man is sitting in the shade. Above him, printed on the dirty window, are the words A PIEBURN. [or P BLACKLAW] Without the full stop, John is reminded of a sign on a cage in a zoo. The old man sits and spits on the pavement from time to time, regarding the cars and passers-by with barely concealed outrage, as if the world were his and his rights were being trampled on. John takes the boxes from the boot and crosses the street, and at his coming the old man gets up and goes inside, John follows him into the dim shop. Inside, it seems that the sunlight is hesitant to come in, as if it is afraid that Pieburn might charge it admission. A bicycle bell pings as the door shut behind John, who stands for a moment to let the world die from his eyes.

[Following taken from unpublished story, “Blacklaw.” Change name and tense to present.]

On the left wall were shelves of paperback books, mostly Westerns it seemed, and piles of old magazines that had the same discarded look as newspapers left on trains. Opposite them were racks of clothes hanging from nails and teapots, pots and pans. The old man, Blacklaw, waited behind a dirty glass counter, watching. Paul was breathing heavily from carrying the bag in the heat, and the old man regarded him sourly, as if there was a finite amount of oxygen in the world and Paul was using more than he was entitled to. [Too much description?] It seemed that everything in the shop had a neat, handwritten price tag, even the carpet at their feet. Most of the prices had been revised up or down several times in red ink. Coming closer to the old man Paul saw he was wearing a worn, but neat, black suit and a creased white shirt. Blacklaw was old, but his face had few wrinkles. He seemed to clench it, so that no one would think him rich in anything, even in years. He would have made love to a shower of gold, like Danae, Paul thought. [Reference too obscure.]

“Aye?” the old man said.

“Would you take these diamonds?” Paul asked. He emptied the diamonds onto the counter.

“Take, oar buy?” Blacklaw asked. He had a strong Scottish accent that he has not allowed Australia to take from him. As he began to sort through the clothes, the old man smiled thinly. He instantly gives the strained impression that he had been smiling for a long time.

“These come from the same place as last time?” Blacklaw asked.

Paul nodded, and Pieburn seemed to appreciate the word that was saved by doing so.

“Then I’ll give you five hundred.”

“All right,” Paul said. Outside, it had started to rain, and the old man looked on with satisfaction at his windows getting cleaned for nothing. [end of “Blacklaw” extract]

Pieburn pays John, and puts the shoes in a milk carton behind the counter., then goes back to his yesterday’s newspaper. John still doesn’t have enough money to pay back X [Mr Chatters/Mr Cohen/Mr Smith] and he is frightened. Then he remembers Jessica’s jewels.

[Climax. John drives home, and Jessica catches John stealing her gold necklace.]

“What are you doing?” Helen Jessica screams.

“Nothing, nothing,” he tries to put the book box away.

“Are you stealing from me?” she asks him. “I told you if you ever did that-“

“No,” he says. Then, “I’m sorry.”

“It’s too late for that now,” she says. “After all this time with you, I feel that my life has been ransacked. I’ve watched you steal from everyone else. You’re not going to steal my life and sell it.”

“I just wanted to see-“ I say.

“You were reading my journal,” Helen says. “You were taking notes, I saw you. You were stealing from my life to use in one of your stories. I can’t take it anymore. I’m leaving. Look at you. Even now you’re thinking about how you can write this. Give me my books.”

I hand over her journals, but she doesn’t notice that I’ve kept one of them back, and a bundle of her love letters.

“Look at you, Phillip,” she says and she is crying. “You’re so full of holes and contradictions. You’re not even a man, just a first draft of one.” [Sounds stagey- but she really said this.]

[And Helen Jessica leaves. In above remember- change journals to jewels. Perhaps suggest Jessica reads a lot, to make sense of her last few lines. John returns to Pieburn’s shop and sells the jewels. He now has enough money to pay off his debt.]

[Last paragraph] “So the wife gave you her stuff tae sell, eh? How is it all writers thieves have understanding wives?” John leaves Pieburn’s shop quickly, feeling that if he stays there too long he will end up with a price tag on him himself, and he has no desire to know his true worth.